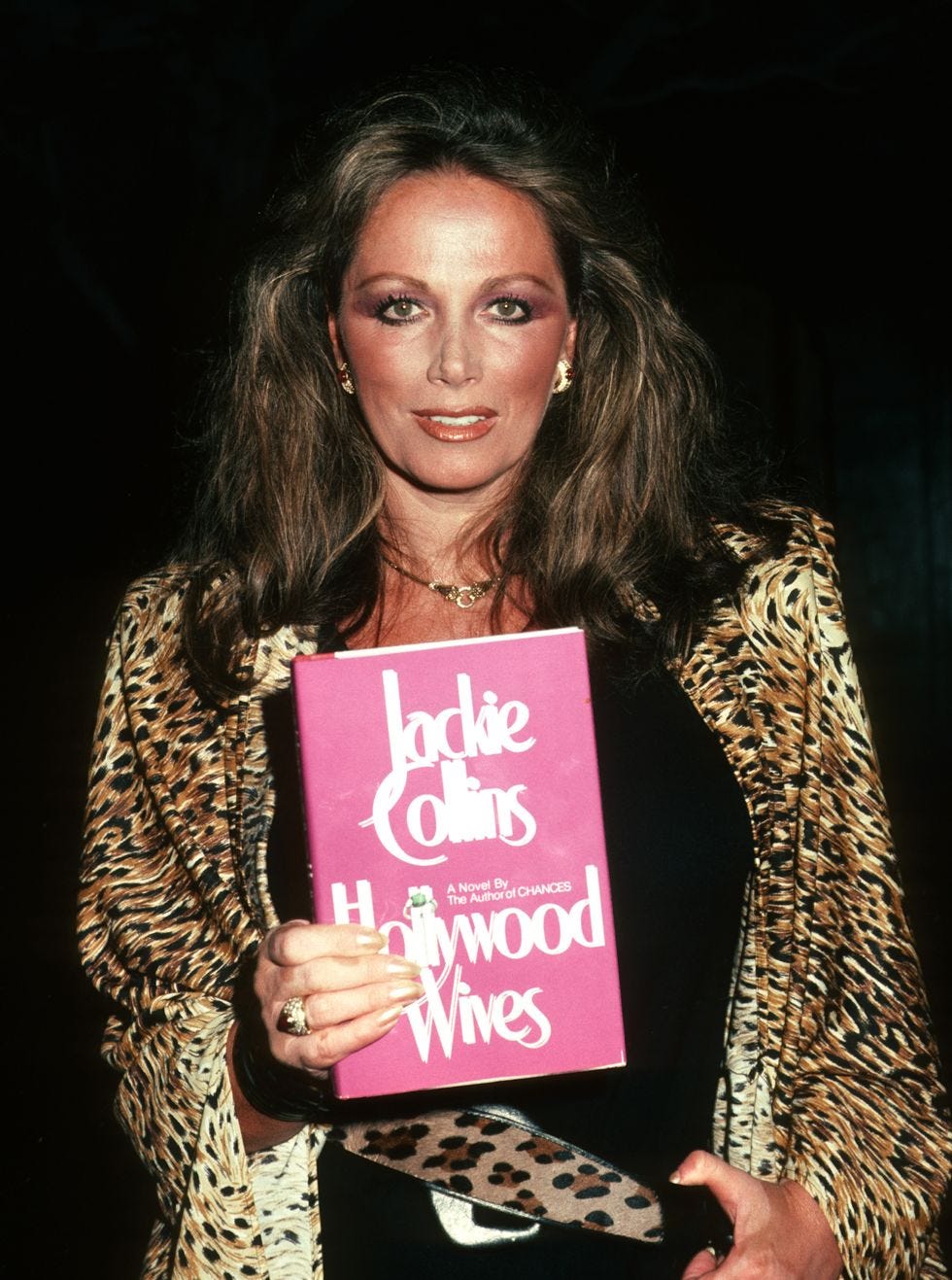

“I’m a high-school dropout who eavesdrops.” That cheeky self-analysis came from one of the best-selling authors of all time, Jackie Collins. She turned her intrusive fly-on-the-wall proclivity into a literary empire built on soapy, twisty page-turners overflowing with style and sleaze. In Hollywood Wives, she focused on the rich, famous, indulged and indulgent of Reagan-era LaLa Land. Forty years after publication, the sweeping epic remains an amazingly juicy read.

Hollywood Wives boasts a whopping 15 million copies sold. No surprise, as it’s likely the best novel ever written that opens with a gruesome triple murder followed by a young man urinating into the swimming pool of a Beverly Hills manse. It maintains that high-octane activity throughout, packed to the gills with sex, crime and labels galore – Armani, Galanos, Sonia Rykiel, Gucci. The book spawned a six-hour Aaron Spelling-produced miniseries starring Candice Bergen, Suzanne Somers and Anthony Hopkins. With the series currently unavailable to stream, it’s hard to imagine just how much of the throbbing and undulating made it to ABC Network primetime in 1985.

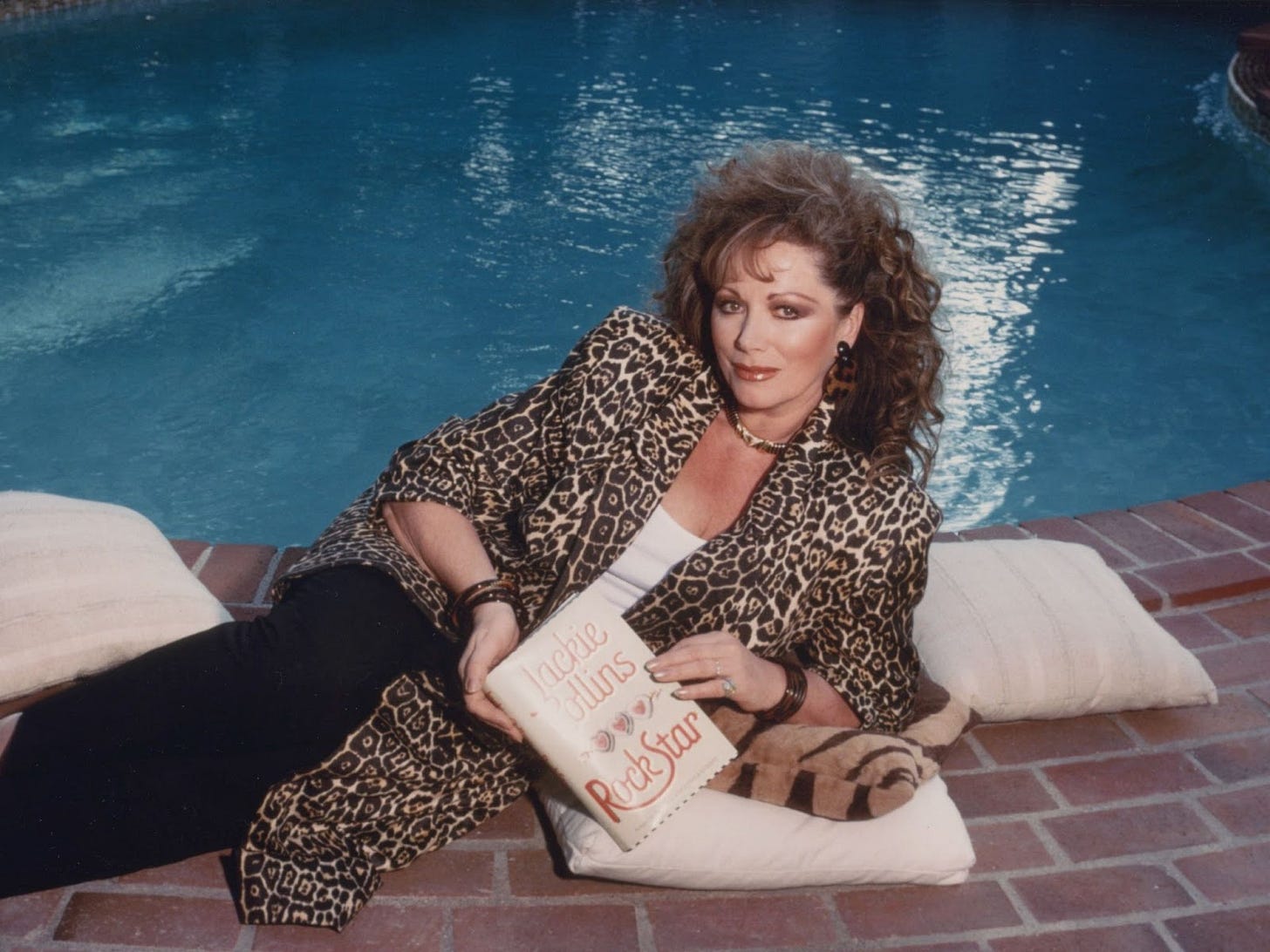

The label-a-minute sartorial references in Hollywood Wives reflect Collins’ legendary appetite for fashion. A lover of leopard prints and diamond-as-big-as-the-Ritz jewelry, she was loathe to repeat outfits. Her collection of custom jackets ran into the hundreds, and she had a particular affinity for Chanel. No wonder then, that the women and men of Hollywood Wives focus on fashion and beauty. They embark on pilgrimages to Saks Fifth Avenue and embrace detailed beauty regimens involving lotions, potions, beeswax extract and regular trips to Elizabeth Arden. Even struggling, up-and-coming actor Buddy Hudson knows the value of a good piece of menswear. He treats his prized Yves Saint Laurent jacket with almost as much affection as his new wife, Angel. When negotiating a fee to act as arm candy for two rich ladies from Texas, Buddy accepts on two conditions: $500.00 a day and a new suit – “Armani.”

Collins’ racy scenes are dizzying in volume and variety: A hot, young Brando-type romantically deflowering his new bride in a Maui hotel. A silver screen-sex goddess and a respected director lunching on “Salad Niçoise followed by solid fucking.” Two wealthy society ladies visiting from Texas attempting to entice that aforementioned Brando-type into their Boston marriage. There are no celibates in Collins’ world, and no nipple size, bedroom technique or penile potency goes unchronicled. Not even the lurid, bloody murder plot gets in the way of the raunchy fun.

Sex was a hallmark of Collins’ work, and she reveled in her reputation as a provocateuse. When Barbara Cartland, the “Queen of Romance,” sniffed that Collins’ books were “filthy and disgusting” and that she was “responsible for all of the perverts in England,” Collins replied with a wryly gracious “Thank you.” She wore such insults with pride, crowing, “Sex is a driving force in the world, so I don’t think it’s unusual that I write about sex. I try to make it erotic, too.”

Any attempt to argue that Hollywood Wives isn’t a trashy novel at heart feels like a rejection of what makes it so compelling a read. It is absolutely a trashy novel, and gleefully so. It is also a kaleidoscopic narrative about a complex group of people whose hometown ethos greatly impacts their life choices and directions. Though Collins might blanche at a comparison to another Brit’s location-specific social epic (so, too, might you, readers, but hear me out), there are shades of George Eliot’s Middlemarch beneath the silk sheets

True, a nineteenth-century provincial British manufacturing town has little in common with the decadent Los Angeles of the 1980s, but sometimes themes rhyme. One such parallel: a woman desperately clinging to her marriage while nurturing her husband’s talents. In Eliot’s telling, it’s Dorothea Brooke, who at the tender age of nineteen, sees a spark of greatness in the much older Edward Casaubon. She marries him and becomes his devoted helpmate as he strives to complete his magnum opus, a theological book entitled The Key to All Mythologies (the title alone should have been a red flag). Whatever affection exists between the two quickly fizzles out, and Dorothea realizes that her marriage has become “a virtual tomb.” Casaubon repays her years of devotion with a middle finger from beyond the grave; a codicil to his will disinherits her should she ever marry her one true love, Will Ladislaw.

Flash forward to late 20th-century Los Angeles and meet Elena Conti, one of Collins’ indelible antiheroines. Elena shed off her humble Bronx roots to become a Beverly Hills housewife. Now married to her second husband, fading movie star Ross Conti, she spirals as she works to resurrect Ross’s career and cling to her hard-fought rung on the Hollywood social ladder. A major element of her plan: throwing the party of the season. It becomes the black hole into which everything else in Elaine’s life disappears – marital struggles, financial woes, nagging self-doubt – as she obsesses over caterers, florists and guest lists like some sort of Galanos-clad Mrs. Dalloway (if Clarissa shared an unfortunate penchant for shoplifting to feel a rush). Ross, in his eternal gratitude, alternates between lazing around the house sniping at her and taking day trips to Century City to bed her best friend.

Dorothea’s heartsickness has some flashes of passion. Her reaction to seeing Will singing with Rosamond Vincy is to “lay on the bare floor and let the night grow cold around her; while her grand woman’s frame was shaken by sobs as if she had been a despairing child.” Elaine works through her grief in a slightly different fashion. First, she attempts to steal a bracelet, and later, “fortified by two Valiums and her new seventeen-hundred-dollar Galanos dress,” she swans through her party maintaining a white-knuckle grip on her sanity (while seating her no-good best friend in social Siberia).

Another similarity: a young couple whose whirlwind romance hits the stormy seas when reality crashes in. Middlemarch offers Rosamond, a girl with big dreams and expensive tastes, and Tertius Lydgate, a dashing young doctor with titled relatives. Their debts pile up and the marriage sours quickly. Hollywood Wives’ Buddy, the handsome aspiring actor who in the past made ends meet as an escort and traded sex for acting lessons, falls hard for the doe-eyed Angel. Their fairytale Hawaiian courtship takes a decidedly un-storybook turn when the couple returns to LA and a life of couch-surfing and audition-hopping. Though unlike Rosamond, Angel remains besotted (and budget-conscious), their tenuous financial situation takes a considerable toll. Desperate for his lucky break, Buddy reluctantly flirts with returning to his hustler past. Salvation comes in the form of Montana Grey, who sees the magnetic talent underneath Buddy’s sex appeal.

Montana is a statuesque cool girl who regards the characters and politics of her Hollywood orbit with an arch, above-it-all remove. She makes a nifty poster girl for the struggle to remain true to oneself and one’s goals in a hostile environment. Eliot’s observation in Middlemarch applies: For those “who go about their vocations in a daily course determined for them much in the same way as the tie of their cravats, there is always a good number who once meant to shape their own deeds and alter the world a little. The story of their coming to be shapen after the average and fit to be packed by the gross, is hardly ever told even in their consciousness.”

Montana remains ever conscious of the dangers of being “shapen.” She arrived in Los Angeles alongside her much older director husband Neil determined to write Street People – a killer screenplay that he will direct. Despite her resultant success, Montana never gets seduced by the trappings of her glitzy new environment. While everyone around her revels in luxe Jaguars, Corniches and Benzs, Montana tools around Sunset in her trusty old Volkswagen (personally relatable). She attends Elaine’s all-consuming soiree wearing an off-beat, all-white combo of silk jodhpurs, leather fringed vest and knee-high boots, an outfit that some onlookers find “incredibly striking.” Not so Neil’s first wife Maralee Sanderson, who fumes that “the woman looked ridiculous in all her fringes and braids. How old was she, anyway?” (Again, Eliot’s narration resonates: “Mortals are easily tempted to pinch the life out of their neighbor’s buzzing glory, and think that such killing is no murder.”) And yet, though determined to march to her own drummer, Montana finds herself swept up in an entertainment industry tale as old as time – the desperate, often futile quest to maintain creative control over one’s passion project.

Both novels teem with an endless parade of memorable characters. One has a pompous auctioneer, a dimwitted but sweet jewelry-loving sister and a divinity student with a gambling problem. The other features a Parisian prostitute turned queen bee of the ladies who lunch, a buxom blonde with a Machiavellian streak and a flamboyant interior designer who procures handsome male escorts for deep-pocketed society ladies (and gentlemen).

Middlemarch is, of course, a classic of the literary canon. A story of a time and place, it also expounds upon evergreen issues of gender, marriage, money and self-determination. So, too, within all its shoulder-padded, 1980s fun, does Hollywood Wives. Collins foregrounds gender politics, flipping some of those tropes on their head. At times, she’s prescient, for example, her men are every bit as concerned with achieving eternal youth as their female counterparts. Today, no one would react to Montana’s script with bemusement that a “broad” can write well. But the newsworthiness of the summer’s biggest blockbuster having been directed by a Greta (and not a Greg) indicates that gender equity in the entertainment world remains a goal. Montana’s story also touches on the ripped-from-the-Deadlines Hollywood tradition of creative accounting. Her passion project falls apart because her producer realizes there’s more money in not making the film at all. “Let me get this straight,” she says. “You’re canceling the film so you can collect the insurance?” An incredulous reaction surely echoed over numerous real-life conference calls in the intervening decades.

Collins may never inspire the scholarly reverence rightfully bestowed upon Eliot. And though Eliot’s masterwork is far more engaging than its dry doorstopper reputation suggests, it can’t match Collins’ level of can’t-put-it-down-for-a-moment zeal. It’s hard to match a sexcapade that ends with the couple requiring surgical separation at Cedars Sinai. Not every novel can have everything. But for all its sex and sleaze (and in part, because of it), Collins’ book, like Eliot’s opus, merits serious consideration as an insightful, masterfully constructed and highly re-readable product of its time.

Ever the canny writer, Collins penned a fitting epitaph for herself, which was honored following her death from breast cancer in 2015. Her tombstone reads: “She gave a great deal of people a great deal of pleasure.” Indeed.