Easter – a time for new beginnings, resurrection, renewal, egg hunts and headgear. Sure, baskets, bunnies and church take up most of the popular imagination around this weekend, but no Easter celebration is complete sans bonnet, with all the frills upon it. And while the Easter bonnet may no longer be de rigueur, plenty of ladies still love to work a spring-has-sprung hat. Literature also has a long history of venerating the chapeau (or at least mentioning it quite a bit). In the spirit of the calendar’s preeminent haberdashery holiday, here’s a look at ten of fiction’s most memorable hats.

HADES’ HELMET OF INVISIBILITY (THE ILIAD; VARIOUS GREEK MYTHS)

Forged for Hades to use in the Olympians’ war against the Titans, this original “say something” hat gets passed around quite a bit. Hades, of course, makes good use of it, as does Hermes, typically while ferrying souls to the Underworld. This earned the helmet the sobriquet “Helm of Death” (not a product name likely to be adopted by the luxury house that shares a name with the Messenger God any time soon). While most flashy toppers aim to attract attention to their wearer, this helmet offers the ultimate luxury – invisibility. In the Iliad, Athena gets to use the helmet to great effect during a battle with Ares. Homer writes, “Athene put on the cap of Hades, to the end that mighty Ares should not see her.” A tactic of questionable honor, perhaps, but one that allows her to get the slip on the God of War. To the bold accessorizer go the spoils.

OFFRED’S WINGS (THE HANDMAID’S TALE)

Margaret Atwood eschews Austinian bonnet-based whimsy, instead offering one of the most memorable, if sinister, literary headpieces ever – the uniform “white wings” worn by Offred and her sister handmaids. A grotesque attempt to protect the modesty of Gilead’s unfortunate child-bearing women, the wings obstruct their wearers’ side vision while reducing them to anonymous, interchangeable broodmares. In her preface to the 2017 version of the novel, Atwood writes that while the visual references to mid-Victorian costume and nuns’ habits were intentional, another prime source of inspiration was 1940s-era Old Dutch Cleanser packaging, “which showed a woman with her face hidden, and which frightened me as a child.”

THE (MAD) HATTER’S TOP HAT (ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND)

Alice in Wonderland’s famous chapeau-wearer got half of his name from Walt Disney. Though the Cheshire Cat tells Alice that the Hatter and the March Hare are “both mad,” Lewis Carroll simply refers to the eccentric tea-party enthusiast as “the Hatter.” Disney may have felt the need to clarify just what kind of Hatter Alice was dealing with, but Carroll likely would not have. Victorian haberdashery was a risky business indeed, one that relied heavily on the use of mercury (hence the expression “mad as a hatter”). Despite his stately top hat, the Hatter takes after some of his less fortunate real-life counterparts. He is by turns petulant and nonsensical: When a spat about watches goes nowhere, Alice finds herself both perturbed and perplexed: “The Hatter’s remark seemed to her to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English.” Alice is not the type to suffer fools gladly (or politely), no matter how proper their headwear. When she takes her leave of the Hatter and his afternoon dining companions, she muses “It’s the stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life.”

THE ABBESS’S TROUSER WIMPLE (THE DECAMERON)

Set against the backdrop of the Black Death, Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron offers up 100 short stories told by ten people hunkering down to avoid the plague. (If one must hide from the Black Death, why not spin yarns in a secluded Florentine villa?) Boccaccio’s presentation of life’s grand tapestry served as inspiration for Chaucer, Shakespeare, Molière and countless others. It also offers up an iconic headwear faux-pas plot twist. Elissa, one of The Decameron’s plague-pod storytellers, narrates the tale of Isabetta, a beautiful, free-spirited novitiate who falls in love with a handsome young man at her convent’s grate. The besotted couple engages in some furtive acts of, shall we say, secular devotion, much to the chagrin of the other nuns. The affair is enough to throw a whirling dervish into a whirl. So, how do they solve a problem like Isabetta? By having the Abbess catch her and her beau in flagrante delicto.

The Abbess, however, has her own secret guy on the side – a priest whom she sneaks into her chambers using a chest. He visits her on the very same night that a cadre of nosy nuns knocks on her door to inform her that Isabetta is, once again, entertaining her gentleman caller. The Abbess leaps from bed and gets dressed, unknowingly grabbing Father’s pants in lieu of her own headwear. Upon catching Isabetta and her beau in the act, the Abbess vilifies “the young nun in terms never before used to a woman.” Isabetta takes her scolding in cowed silence until she sees “what the Abbess was wearing on her head, with suspenders dangling on either-side.” Chastity may be a virtue, but so, too, is charity, and Isabetta possesses the latter in excess. “Mother,” she entreats the Abbess, “God help you, but tie up your wimple, and then tell me what you will.” Realizing her predicament, the Abbess has an epiphany of her own: The spirit may be willing, but the flesh is, well…you know. She then decrees that everyone at the convent should “enjoy herself whenever possible, provided that it be done as discretely as it had been until that day.” An all too-common tale of the hypocrisy of bad habits.

HOLDEN CAULFIELD'S HUNTING CAP (THE CATCHER IN THE RYE)

Like any angst-ridden teen, Holden Caulfield channels his search for identity into a statement look. While on a trip to New York, he loses his fencing team’s equipment, and engages in a little retail therapy, buying himself a kicky, red hunter’s cap (and for only a buck!). The hat quickly becomes a signature item, offering Holden the opportunity to telegraph his individuality – wearing it backwards, appraising his “stupid face” with it on in the mirror – as well as his often macabre sensibility. When Ackley mocks him for wearing a “deer shooting hat,” Holden combatively replies “Like hell it is…This is a people shooting hat.” Despite his posturing, Holden is vulnerable to the all too-common adolescent tension between wanting to look defiantly singular and not wanting people to think you’re a total boob. En route to the Edmont Hotel, he keeps his hat on in the privacy of the cab but removes it before check-in, saying, “I didn’t want to look like a screwball or something. Which is really ironic.”

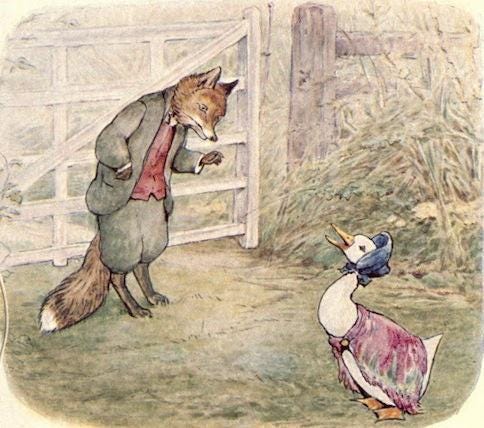

JEMIMA PUDDLE-DUCK’S BONNET (THE ADVENTURES OF JEMIMA PUDDLE-DUCK)

“Jemima Puddle-Duck was a simpleton.” A cruel, but true, character assessment, Fortunately, what Beatrix Potter’s wayward waterfowl lacks in common sense she makes up for in demure style. Indeed, Jemima is part of a grand tradition of flighty fictional bonnet aficionadas. (Pride and Prejudice’s Lydia Bennet is a bird of a similar feather). Unfortunately, Ms. Puddle-Duck’s prim headwear offers little in the way of protection from the charming, nefarious woodland fox with whom she unwittingly finds herself shacking up. He sends her out to pick herbs for an omelette, a mission happily interrupted by a collie who, upon recognizing that Jemima is procuring the exact ingredients for roast duck, comes to her rescue.

CLARISSA DALLOWAY’S NOT THE RIGHT HAT FOR EARLY MORNING (MRS. DALLOWAY)

Haberdashery looms large in Virginia Woolf’s classic. The doomed Septimus Smith helps his wife Lucrezia design a hat shortly before his suicide. It’s an aching moment of connection -- Lucrezia is thrilled to share a sliver of marital happiness with her troubled husband -- that ends in tragedy. The titular Clarissa Dalloway has a different kind of character-revealing, headpiece-induced reverie. Immediately upon leaving her house in the novel’s opening pages, Mrs. Dalloway runs into Hugh, a lifelong acquaintance with his own tale of woe. He’s come to London to bring his often-ill wife to the doctor. Clarissa does her best to offer a sympathetic ear, but quickly finds herself “oddly conscious at the same time of her hat” – not the most empathetic train of thought, nor the most admirable. But it is “not the right hat for early morning,” and who among us hasn’t allowed the mind to stray from topics of import when confronted with the possible inappropriateness of a wardrobe choice?

FORTUNATUS’ WISHING HAT (THE PLEASANT COMEDIE OF OLD FORTUNATUS)

A figure of Germanic legend and titular star of Thomas Dekker’s 1599 play, Fortunatus is a pretty lucky guy. A beggar he meets turns out to be the goddess Fortune in disguise. She offers him the classic choice – wisdom, strength, health, beauty, long life or riches. He chooses the riches and receives an infinitely self-replenishing purse. Later, he visits the Soldan of Turkey and, in an extremely ungracious display of guest behavior, tricks his host out of a miraculous hat that whisks the wearer wherever he wishes. Fortune’s bill comes due, and Fortunatus dies wealthy, and be-hatted. His two sons (one representing Vice, the other, Virtue) split their inheritance – one takes the purse, the other the hat. Through a series of ill thought-out decisions, the brothers lose both – swindled out of them by Agripyne, the princess that one of them attempts to abduct. She gets to relish her victory, delightfully proclaiming to have “Wealth in my purse, and knowledge in my hat.” More machinations ensue. One brother is transformed into a beast, then turned back; the princess is abducted then escapes; the duo regains their inheritance. Finally, faulting their misfortune not on recklessness or lack of foresight, but on the hat, the virtuous brother burns it. It is a poor craftsman who blames his toques.

SABINA’S BOWLER (THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING)

When is a hat more than a hat? Why, when it is a “motif in the musical composition that was Sabina’s life.” In Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Sabina’s hat returns “again and again, each time with a different meaning.” It is by turns a family memento, passed down from her grandfather and father; a representation of her closely cultivated originality; a sentimental reminder of her own past; an occasional symbol of “violence against her dignity as a woman,” and, perhaps most strikingly, an object of erotic fetishization. Is a bowler the sexiest hat? Well, it certainly helps if that bowler is frequently worn for adulterous hotel-room trysts, typically paired with bra, panties and nothing else but confidence.

LEOPOLD BLOOM’S HIGH QUALITY HA’ (ULYSSES)

Is Ulysses the greatest Western novel of the 20th century? Perhaps. Is it the greatest hat novel of the 20th century? Absolutely. Leopold Bloom’s Dublin is a city of hats, or people in hats, more accurately. There’s Stephen Dedelus’s “Latin Quarter hat,” Buck Mulligan’s Panama and Blazes Boylan’s straw number. One hat looms large though, and that’s Leopold Bloom’s bowler. James Joyce practically introduces Bloom contemplating his headgear, so well-loved that the interior label has worn down, simply reading, “Plasto’s high grade ha.” Bloom’s hatband is good for more than wordplay (“hat” to “ha” – some low hanging fruit for Joyce), it also keeps his secrets in the form of a “White slip of paper” tucked within. That white slip of paper is being kept “Quite safe” for good reason – it’s the calling card for Henry Flower, the alias under which Bloom receives his adulterous correspondence. Joyce being Joyce, this isn’t the only time that hats become cover for something sexual. A brothel hat rack becomes a metaphor for Bloom’s or cuckolded status; that straw hat looms large whenever Bloom thinks about his wife’s trysts with Boylan. Indeed, by the time Molly Bloom notes that her husband is “ever wearing the same old hat,” it’s hard to believe that she’s only referring to his chapeau.

Through all the trials, tribulations and flights of fancy of one ordinary man’s extraordinary day, Bloom has his bowler by his side. Well, up until the wild, weird, hallucinatory fashion show in the “Circe.” chapter. Then, he switches hats with abandon as he slips through different versions of himself – there’s a “grey billycock hat,” a purple Napoleon hat and a fez, among others. Ultimately his trusty “high grade ha” betrays him when, during one of his many interrogations, his Henry Flower calling card falls from its band, laying bare his seedy peccadillos. The hat may taketh away, but it also giveth. Later, after Bloom is declared to be “virgo intacta,” (derogatory), it offers some protection when “Bloom holds his high grade hat over his genital organs.” The potent erotic symbolism of the bowler – who knew?